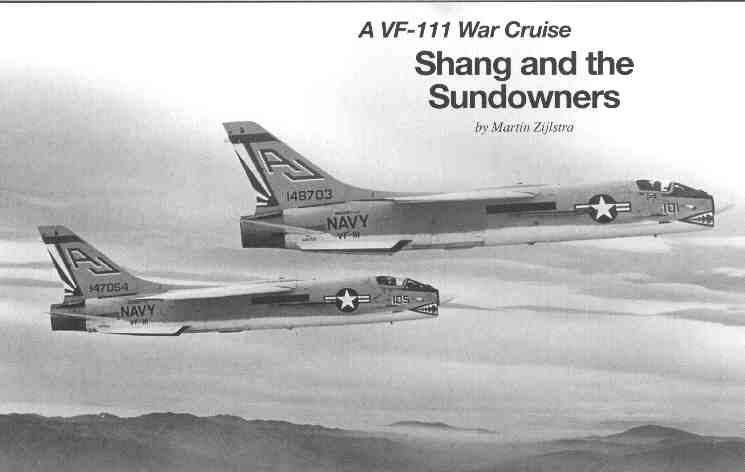

ABOVE: A section of the Sundowner F-8Hs shows the renowned color scheme worn during their service with the USS. Sahngri-La (CVA-38) on the carrier’ final deployment, Mar-Dec ’70. Photo courtesy RADM James B. “Red” Best USN(Ret)

When USS Shangri-La (CVS-38) left its pier at Naval Station Mayport Fla., on the morning of 5 March 1970, a remarkable WestPac deployment had begun. Not only was it the final cruise for the veteran carrier, but it was also the last for Fighter Squadron VF-111 in the venerable F-8 Crusader. For Sundowners CO, CDR Charles Dimon it was to be his fifth Vietnam combat deployment, whereas others were on their first.

For VF-111, it was to be the seventh visit to the stormy waters off Vietnam. The squadron had deployed in Midway (CVA-41) with CVW-2 in 1965, Oriskany (CVA-34) with CVW-16 in 1966 and again in 1967-’68 and Ticonderoga (CVA-14) with CVW-16 in 1969. A special VF- 111 Detachment 1 made two deployments in Intrepid (CVA-11) as pant of CVW-l0.

On this seventh deployment, the Sundowners were part of Carrier Air Wing Eight, an East Coast air wing made up of VF-111 and VF-162 (F-8H), VA-172 and VA-12 (A-4C), and VA-152 (A-4E). Detachments included VAW-121 (E-IB), VFP-63 (RF-8G), VAR-b (KA-3B) and HC-2 (UH-2C).

To Vietnam the Long Way Around

VF-111 was aboard with only four aircraft, seven pilots and 97 enlisted men when Shangri-La sailed. The remainder of the unit, eight aircraft, 10 officers and 82 enlisted men, remained behind at NAS Miramar for 22 days before flying to NAS Cubi Point under the leadership of the XO, CDR Bill Rennie. CDR “Stinger” Dimon was among those that sailed in Shangri-La with all pilots scheduled to leave the squadron during the cruise. CVW-8 flew many training sorties on their way to Southeast Asia, but not all were without incident.

On 9 March, a VF-162 Crusader crashed into the sea northeast of French Guiana and its pilot, LTJG F.C. Green III, was lost. Five days later, life took a more pleasant turn in the form of a port call at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. CDR Dimon remembers it as fun.

“The night we departed, I came back to the ship on the so called ‘last boat.’ When I came aboard, I suggested they run another boat, as there were still quite a few people on the beach, and the ship’s XO was asleep in his cabin. The logistics to get them from Rio to Cubi Point, our next stop, would have been a nightmare. Although the XO did not like my suggestion very much when he found out, and really chewed on me the next day, I felt I was right, since no one was left behind.”

After rounding Cape Horn, Shang set course for the Philippines and anchored at Subic Bay on 5 April 1970, the point where both elements of the Sandowners would join. Chuck Dimon remembers:

“Before leaving Miramar, the squadron managed to ‘procure’ a pickup truck and a Falcon sedan for official and unofficial transportation. We were also fortunate enough to acquire a whaleboat from Navy surplus before leaving California, probably making the Sundowners the only fighter squadron in the world with its ‘own’ navy. Both the vehicles and the boat were shipped to the Philippines courtesy of Samuel Gompers (AD-37). I flew in early that day to meet Bill Rennie and the other guys. Bill had it ready to go girls for show even we went out drinking beer and having a grand old time to meet Shang coming into the harbor. CAPT Herbert R. Poorman, the CO of the carrier, came up on the 5MC and told me that I would never fly in early again he was just kidding of course, as he was a nice guy.”

On an other occasion, CDR Dimon had to report to CAPT Poorman’s offices again. “Our boat developed engine problems, so Bill Rennie or one of the chiefs sent it to the Subic shipyard for an engine overhaul and upkeep. About a month later, CAPT Poorman called me in and asked me about $2,700 billed to the ship for the work done. I smiled and said, ‘Hey boss, we just gave you a new motor whaleboat.’ They kept it and used it during the rest of the cruise.”

Pilots transPac’ing their F-8s from NAS Miramar to Cubi Point, R.P. From l to r: CDR William B. Rennie (XO); LCDR’SJames B. Best & Neil Donovan(neeling) LT’s Hugh J. Risseeuw, George Melnyk & Robert H. Kiral. Photo: courtesy of CDR. Chuck Dimon, USN(Ret)

In the War Zone

After three days in Subic, Shangri-La returned to sea on 8 April 1970 and continued toward Yankee Station. At 0500 on 11 April, flight quarters were sounded for the first combat sorties, and Dimon was chosen to lead the first one.

“It was another Shang disaster,” Dimon recalls. “Her call was AllStar but we would always check in with ‘Allstate.’ Though this was my fifth Vietnam cruise, our CAG had only been to ‘Nam as air boss – he’d never flown while there. So he picked me.”

The weather was lousy-fog to deck – and CDR Dimon and his wingman LT George Melnyk were launched for a weather recce.

CDR. Chuck Dimon CO of the VF-111 Sundowners, celebrates his 600th Crusader trap, 23 May ’70 on board The USS. Shangri-La

Photo: courtesy of Capt. Charles G. Dimon, USN(Ret)

“I went up into the Gulf and looked around. It was a definite no-go, and I recommended not to launch. We started returning to the ship when we heard other aircraft checking in. Things like, ‘No targets, dump ordnance.’ The ship requested I make an approach to see how the weather was, but it was all below minimums, and since we had no ACLS, we had to bingo to Da Nang. The other aircraft-I think they came from Constellation had the same problem, and they also had to go for Da Nang. The weather at Da Nang was also IFR, so everyone had to make an approach, which meant that there were a lot of low fuel state aircraft in the air. One A-3 had a hell of a time and flamed out when finally clearing the taxiway.”

The landing of Dimon and his wingman at Da Nang also was not without incident.

“Melnyk had no radio, so he relied upon me. I got him down at Da Nang-on our approach I broke out of the goo at about 300 feet, saw I was lined up slightly off the center, gave him the power signal with a head nod, eased over the center line, then head-nodded back on power.

“As I touched down, I noticed he passed me and took off again-no radio and no way to get back on deck. So I put on power again, took off and joined him. I took the lead again and got the controllers to sneak us in and landed with the low fuel lights-my, oh my-great. That was my first combat leg from Shang, a remarkable one!”

During the first line period, Shangri-La operated on a flight schedule that began at noon and lasted until midnight. After a week, this was changed to midnight to noon. Whatever the timetable, more than half the flying was at night and often under adverse weather conditions. During this period, 11 April until 2 May 1970, the air wing flew recce missions over Laos and North Vietnam, giving the Sundowner pilots many escort missions. However, the vast majority were BarCAP missions, which proved the trend of the entire cruise.

USS. Independance (CVA-62) steams with the Shangri-La with both flight decks spotted artistically rather than operationally, 1968. Photo: courtesy of USN James R. Szenasy

No-Radio Night Recovery

Flying 12-hour schedules makes night flying a routine, although not a pleasant one. LT Ken Mattson assigned to the CO as Stinger Two- was one of the four new pilots assigned to the Sundowners before the start of the cruise, and he had his share of experiences.

“One day I was to be wingman to John L. Black Jack’ Finley on a midnight or 0200 BarCAP flight. I launched after him, and immediately after the cat shot, my radio quit working. I turned on the anti-collision light and joined up with my leader climbing to 16,000 feet, our squadron safe altitude. I hooked up my PRC radio to my earphone, turned to the emergency radio frequency and talked to Black Jack. He confirmed that my hook was down then told me to recover in 15 minutes. He proceeded north with the spare pilot that had been launched, leaving me alone to make it back to the boat. I dumped fuel and went to afterburner to get down below max trap weight. I then headed to the initial point [IP] five miles behind the ship at 1,200 feet and started my CCA. I can hear them, but can’t answer.

“My first pass didn’t work-I can’t remember if the deck was fouled or if I wasn’t looking good to the LSO. I returned to the IP to do it all over again, and again I did not get aboard. I remember being frustrated because I was now getting low on fuel and would have to divert to Da Nang soon. It was a clear night, and I wasn’t going to let the boat get me in trouble. After the second pass, rather than clean up the gear and cruise back out to the IP, I disconnected my PRC radio from my headset and climbed to 400 feet, the daytime pattern altitude, and came around to do what I did best-get aboard the boat.”

As “Rocket 3,” Mattson was the junior pilot, which meant that he was automatically assigned as CDR Dimon’s wingman. During the cruise, Mattson made 120 traps, 22 of them at night, and logged a total of 260 hours. He remembers that the average ready room briefing started one hour before the scheduled takeoff time, and that every trip was followed by a 30-minute debrief, depending on the time the LSO needed to make the rounds of other ready rooms.

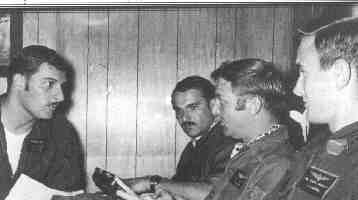

Lt Chuck Scott (left) responds to a comment by flight leader LCDR James B. “Red” Best prior to a mission over North Vietnam. Others include LTs George Melnyk (2nd from left) and Randy Anderson. Photo: courtesy of RADM James Best USN(Ret)

Ramp strike

The air wing lost two A-4s and a VF-162 F-8 in the first line period, and two of the three pilots involved survived their mishap. The line period was followed by eight days of R&R at Cubi Point, a place to become a familiar sight for the Sundowners. Shangri-La returned to sea bound for Yankee Station, where for VF-111 the second line period operations were essentially unchanged. There was an increase in the number of Blue Tree missions, giving the sundowners more escort missions over North Vietnam. One of the highlights of this period was the 600th F-8 trap of CDR Dimon on 23 May. Upon recovery, he was met by CAPT Poorman at the aircraft and later cut a giant cake together with XO Rennie.

Following these festivities, the dangers of carrier aviation became clear again when CAG hit the ramp on an approach on 28 May. CDR Dimon remembers both the accident and the circumstances that led to it.

“CAG did not fly very much. He had not had a night trap for, I think, more than three months. CAPT Poorman wanted him to fly more, so CAG came to me. We set him up with a pinky [early night trap], not forcing him to get back aboard the ship in the pitch black. On preflight, however, he downed the aircraft because of a problem with fuel gauge fluctuation.

“I saw him the next day or even that night and told him that we would set him up again. He instead wanted to go to VF-162 and they set him up with a late go. I got a call in my room when he had crashed-he struck the ramp on recovery-but was happy to hear that he was OK. Re was very lucky to walk away.”

The next morning, however, CAG walked into the Sundowners’ ready room without his wings. “We got to the comer and he told me that I was to be the new CAG until his replacement arrived,” Dimon continued. “So I acted as CAG until CDR Ed McKellar arrived to relieve me”.

Only days later CDR Dimon was witness to another mishap that seemed increasingly typical for Shangri-La during its final cruise.

“The ship already had problems from the moment it left Mayport,’ he recalls. For starters, the Tacan was inoperable for the first three or so months. In fact, young pilots such as Ken Mattson considered the ship to be more of a threat to them than the war or the weather. On 30 May, while moored in Subic Bay after the second line period, CDR Dimon asked CAPT Poorman whether he would like to fly with him.

“He said ‘hell, yes’ and we took off to observe the mining of a target near Cubi. I let him lead for a while and just hung on. The moment we were overhead the mining, we were told to come back to Cubi ASAP as the ship had a problem. Away we went.

It appeared a firemain in the refrigeration area of the ship had ruptured and flooded the spaces, causing extensive damage to the refrigeration units. CDR Dimon remembers the flight as a short hop for the skipper and an interesting one for him: The mining results had been poor and the attack squadrons flunked ORI!

Trouble Again

After almost two weeks, Shangri-La and CVW-8 set to sea again for the third line period after two days of carquals in the Philippine operating area. In June, Chuck Dimon was relieved by CDR Ed McKeller as CAG, leaving Dimon to remove one of the two hats he had been wearing. The third line period was essentially the same kind of flying, and was to remain so for the remainder of the cruise. With no MiGs showing up, the pilots of VF-111 and VF-162 flew lots of BarCAP and recce escort trips.

Ken Mattson, who started as a WestPac rookie, became more experienced with every mission, and was soon assigned to fly escort for VFP-63 photo forays.

“I remember one trip into Laos,” Mattson recalls. “We’d normally fly high cover behind the photo bird to protect his six. During this mission, the photo guy had me come down low and took my picture against a waterfall in Laos. I had a grand time shooting my guns and so on.

“However, when the skipper saw the resulting photo, I was in deep trouble.”

The third line period proved to be a bad time for the air wings’ safety record. During the first two line periods, CVW-8 already had lost or damaged two F-8Hs, one E-1B and three A-4s. During the third period, which started on 14 June and ended on 2 July, two more Skyhawks and an E-l suffered mishaps, which luckily did not result in all cases in the loss of aircraft or human life.

On 2 July bad luck struck Shang again when the carrier suffered a sheared shaft coupling on the No. 1 shaft. After a transit to Subic Bay to remove the screw, the carrier proceeded to Japan for an extended dry-dock stay at Yokosuka. The same day Shangri-La left Subic Bay for Japan, CDR Rennie relieved CDR Dimon, who had orders for Naval War College. CDR Harlan Pearl arrived as the new Sundowners’ XO.

Sundowners at ease in their ready room include (kneeling, from left)LTJGs Dean Baird, Tom Williams, Ken Mattson; LT Bill Curran. Standing L to R: LTJG Rick Hadden; LT Jim Kinslow; CDR Chuck Dimon; LCDR Jack Finley & LTJG Brian Wagner. Photo: courtesy of CAPT. Charles G. Dimon USN (Ret)

A Good Deal Times Two

Leaving Japan on 23 July, CVA-38 set course for Yankee Station again, and the daily schedule returned to the routine of many weeks before. People may have thought that Shang was haunted, because only days later, bad luck struck again. In the afternoon of 29 July, a fire was reported in the starboard steering engine unit. Although it was extinguished quickly, the ship had to be steered by engines alone for more than three hours.

On 5 August, the operating periods changed from noon to midnight. Squadron operations were generally the same as before, although the weather over the beach had deteriorated, leaving the pilots almost without any other missions than normal BarCAPs.

In early September, LTJG Randy Anderson, having just finished RAG, had orders to report to the Sundowners and travelled to Southeast Asia together with LTJG Richard F. Burns, who was assigned to the Sundowner’s sister squadron, VF-162.

‘We flew from Travis AFB to Clark AB and then took a Hercules to Da Nang. As we deplaned and walked across the ramp, there was an air strike dropping napalm right off the end of the duty runway.

“I remember turning to Dick saying ‘Welcome to the big leagues.’ From Da Nang we took the COD to Shangri-La

.” During September, October and November, Anderson flew mostly BarCAP missions, feet wet, between the ships of the 7th Fleet and the coast of North Vietnam. ”

Occasionally we did escort missions along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and into the passes that lead into North Vietnam from Laos. My first photo-escort was one to remember. As this was my first trip into North Vietnam and I had only been out of the U.S. for 30 days, I was somewhat apprehensive.

“I was escorting a RF-8G, call sign Corktip, flown by-if I am correct- C.A. Simpson. We had to make photos of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and through the Ban Kari Pass into North Vietnam. My job was to fly a tight combat spread formation about 3 or 4,000 feet abeam Corktip. From that position I could warn him of hostile aircraft or AAA, leaving him to concentrate on his cameras. Now that I think of it, I was checking his six, but mine was unprotected…..”

Anderson remembers it as an overcast and rainy day, forcing them fly below the cloud layers as he went into the Ban Kari Pass.

“The clouds came almost down to the walls of the pass on both sides as we flew through it and rather further into North Vietnam than I thought we were supposed to. I felt relieved when the run was over and we regressed back into Laos. Only then did I hear C.A. say, ‘Whoops, I forgot to turn the cameras on, we’ll have to do it all over.’ I was very green, but knew it was a good military principle not to do the same thing twice. But we did it, including the incursion into North Vietnam. To this day, I think C.A. did it over on purpose just to see if I’d go back with him.”

R&R in Hong Kong

The fourth line period was followed by some rest and relaxation in Cubi Point again. For most of the Sundowners, the naval base and its surroundings became quite familiar, since one or two aircraft were at Cubi most of the time for corrosion control and flight checks, and one, as Ken Mattson recalls, was always a hangar queen. Only a few days into the fifth line period, CAPT Poonnan was relieved as CO of Shang by CAPT Hoyt P. Maulden.

Apart from an A-4 crashing into the sea after a faulty cat shot, this line period and the next, the fourth and fifth, were uneventful. Another highlight, however, was the port visit to Hong Kong, BCC. After one week of R&R, the crew was at sea again for Yankee Station for the sixth and final line period.

Until that moment, most of the squadrons of the air wing had encountered their share of mishaps. However, the Sundowners had not been involved in anything major. On Halloween 1970, the CO, CDR Bill Rennie, personally ended this record. Upon return, his Crusader skidded to a stop in the wires due to a collapsed nose gear, an accident not unknown to F-8 pilots. Luckily, it was only a minor mishap, and was ruled a simple material failure.

At 1800 on 6 November, the final line period ended and Shangri-La anchored at Subic Bay. During the cruise, VF-111 had been on Yankee Station for 124 days, had flown 109 combat sorties and 1,191 support sorties.

Sundowners F-8H patrols South Vietnamese skys near DMZ. Photo: courtesy of RADM James Best USN(Ret)

The officers and men of VF-111 left the carrier and transPac’d back to Miramar rather than sailing all the way back to Florida. The transPac via Guam, Wake and Hawaii was supported by maintenance crews on two C-118s and one C-121 The remainder of the unit returned home on a DC-8 and a C-141. Although there was some delay due to logistical problems, the trip back home marked the first time an aviation squadron’s entire assets were flown from WestPac to the U.S. West Coast. The Sundowners set foot again on NAS Miramar on 23 November, thus ending a remarkable cruise.

And on 14 December, three days before Shangri-La returned to NavSta Mayport from its final cruise, the first pilots of VF-111 were busy again and began transition to the F-4B Phantom II.

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank former Sundowners Chuck Dimon, “Red” Best, Ken Mattson and Randy Anderson for their assistance. Also a big “thank you” to the other Sundowners involved and Henk van der Lugt of the Sundowner Association.

Martin Zijlstra, a 41-year-old major in the Royal Netherlands Air Force, currently serves as editor of its official monthly, the Flying Dutchman magazine. In his spare time, he specializes in researching the history of Carrier Air Wing Eight. For his next project he would like to get in touch with any aircrew that sailed with USS Nimitz (CVN-68) on its Mediterranean/Indian Ocean cruise of 1979-1980.